Ski jumping in a fight to survive in Canada

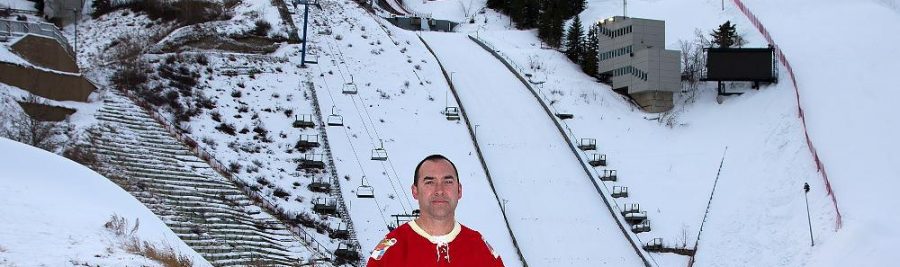

Unbeknownst to him, the night before at an AGM in Calgary he had been voted in as the new chairman of Ski Jumping Canada. He had agreed to let his name stand for a board position, but this was a little unexpected.

Soon, he realized his role was to be far greater than that: Saving the organization from extinction.

“I was a little bit perturbed (that I’d been named chair),” said Reid, who was being groomed for the position as a past-chair of Ski Jumping Alberta, “but I thought ‘what the hell, I figured I was ultimately going to end up there anyway, why not now?’

“So I got copies of their financial statements … and immediately had a heart attack.”

Fresh off being shut out by Own the Podium for a second year in a row, Ski Jumping Canada was in dire straits.

“Effectively, we had zero revenue,” recounted Reid, noting not only did OTP bat a blind eye, the group also lost its longtime Olympic Legacy Coaching fund, which had paid for their coaching since the 1988 Games in Calgary. “And we had about $20 or $30 grand in the bank.”

Reid was blunt at the new board’s first meeting: “I said ‘guys, we’ve got about three or four months and we’re bankrupt.’ We are out of business. There will never be ski jumping in Canada … unless we do something.”

One of Canada’s oldest Olympic sports was on the verge of fading into the history books.

“Without Tom, I have no idea where we’d be,” said head coach Gregor Linsig. “I don’t think there’d be a Ski Jumping Canada right now without him.”

Reid, whose day job is senior vice-president, Western region for Aviva Canada, immediately went into penny-pinching mode. He decided coaching expenses — including paying for Linsig and their portion for an overseas coach they share with the Americans (Bine Norcic) — were priority No. 1.

“The good news is we’re in a better place now,” Reid explained. “We’ve done a few things since then. One of the things that we did is we got this marketing committee together, which consists of myself, a gentleman who runs a small IT consulting firm and a gentleman who runs a medium-sized oil and gas company in town. We started to pool our contacts.”

They got a networking breakfast together, which allowed national team athletes to meet sponsors. Aviva paid for it. WinSport executive v.p. Steve Norris donated his appearance as keynote speaker. And the organization raised $12,000, including Rogers Insurance backing national team athletes Matthew Rowley and Taylor Henrich. Mackenzie Investments has also stepped up with major sponsorship through the Snow Sports Consortium.

“If you look at where we were historically, it cost about $220,000 a year to pay all the bills for Ski Jumping Canada,” said Reid. “And right now, we’ve probably got about $60 or $70,000 that’s committed annually for the next four years. That pays for our coaching. So we’ve cut our costs down to the absolute bare minimum.”

Reid calls it the subsistence level, essentially survival mode. And that hasn’t been easy on the athletes, who once were offered incentive pay (World Cup points equalled travel costs being paid). Now they need to come up with their own travel costs — about $10,000 to $15,000 a year each.

On top of that, the only way to attract government funding again is to get results (OTP’s longtime mandate), but Canadian athletes are going against big-budget European outfits without access to the same advanced training opportunities.

“What we’re missing — I don’t think we’re ever going to go back to a place where we’re subsidizing the athletes like we used to — but what I want to do when we get more money, is I want to get some improved training for these guys, like a strength and conditioning coach,” said Reid, who is aiming for more sponsorships.

“We need sports psychology, need access to what’s called an integrated support team, which includes medical.”

Already, top athletes have left. Alexandra Pretorius, who won two Grand Prix events in the summer of 2013 before a knee injury caused her to miss the Sochi Olympics where she would have been in the podium conversation, retired in October at the age of 18. And Mackenzie Boyd-Clowes, who has been Canada’s top male jumper for the past few years, is taking a year off.

“It’s very hard for them to comprehend,” said Linsig. “To do the sport that they love but they have to get a full-time job, go to school … travel the world all on their own dime. It’s impossible. That totally reflects on their decision to continue.”

The current national team members, who are committed to Reid’s plan, have had to pick and choose which competitions they’re going to this season.

Rowley is attending his first World Cup of the season in Switzerland this weekend — (he was 59th in Friday’s qualifying in Engleberg) — before heading to the prestigious four-hills tournament.

The women’s team, which consists of Henrich and Jasmine Sepandj — (veteran Atsuko Tanaka blew out her knee on her first jump of the summer and her season is in jeopardy after a car accident last month) — won’t compete until January in Sweden.

The rest of the men — Trevor Morrice, Dusty Korek, Josh Maurer and Matthew Soukup — will aim for a January competitive start, too.

And Linsig will be bouncing around between all the athletes, including helping those on the provincial team and national Nordic Combined squad — Wes Savill and Nathaniel Mah.

It’s not ideal, but it’s all they can do to survive. A shame, considering their potential — the Canadians outperformed the Russians at the Sochi Olympics with just 5% of the hosts’ budget. Tanaka had the best individual result, a 12th in the inaugural women’s Olympic event — just 14 points shy of a medal on a packed leaderboard.

“I think over the past four-to-six years, we’ve been making great strides and we’ve been hitting our target goals and we’ve been improving every year,” said Linsig. “We want to continue that and it’s a little bit different now with the funding (gone).

“I don’t see why we can’t as long as we have the athletes dedicated to continue. That’s the main thing. If we can show them we’re trying to find money, I know they’ll stick around and give it their best.

“I want to see this sport survive, obviously. It’s all our lives, our passion. If we were to go, then it would be devastating for a lot of people.”